Three more children die in unexplained acute hepatitis outbreak

Three children in Indonesia died from acute hepatitis in April, the country’s health ministry announced on Monday.

The news brings the death toll from the unexplained outbreak of liver inflammation in children to at least four, after another death was confirmed by European health officials last week.

The children, who were admitted to hospital in Jakarta, showed symptoms including nausea, fever, vomiting, jaundice, diarrhoea, seizures and loss of consciousness, the Indonesian health ministry said in a statement.

Singapore confirmed its first case of acute hepatitis in a 10-month old baby on May 1, according to Bloomberg, while Japan’s health ministry said it believed it had identified a possible case on April 26.

Severe hepatitis, or liver inflammation, is rare in young children. The current outbreak has led to at least 17 liver transplants in patients aged under 16, and one death, according to the World Health Organization (WHO).

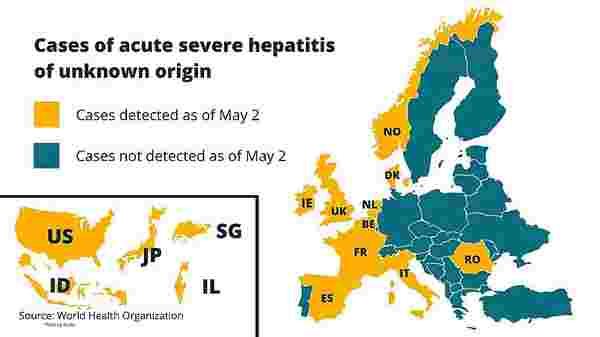

There are now almost 200 cases of unexplained severe hepatitis affecting children around the world, European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) director Dr Andrea Ammon said on April 26.

Britain is the country worst-affected, with 111 cases at the last count.

Around 55 “probable or confirmed” cases have been identified in the European Union and European Economic Area, the ECDC said.

Cases have also been confirmed in the United States and Israel.

“Investigations are ongoing in all the countries reporting cases but at present the exact cause of this hepatitis still remains unknown,” Ammon told a press conference in Stockholm.

She added that there is currently no known link between the cases, or any connection to travel.

The ECDC declined to confirm in which country the first confirmed death had occurred, telling Euronews Next that the information was “confidential”.

The UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA) has said that no hepatitis deaths among children have been recorded in Britain.

Countries where cases of acute severe hepatitis of unknown origin have been detected are marked in yellow.Euronews Next / Canva

Countries where cases of acute severe hepatitis of unknown origin have been detected are marked in yellow.Euronews Next / CanvaAdenovirus to blame?

While the possible cause is not yet certain, Ammon named adenovirus – a common virus that typically causes flu-like or gastrointestinal symptoms – as a possible trigger for hepatitis in the affected children.

“The investigations right now point towards a link to adenovirus infection,” she said.

Hepatitis is usually the result of a different infection by the hepatitis A, B, C, D or E viruses, but signs of these have not been present in the cases identified worldwide so far.

Asked whether the uptick in hepatitis cases among children was simply a result of increased monitoring, Ammon said that it was unlikely such infections would have gone unnoticed in the past.

“A baseline number [of cases] is difficult to do because the adenovirus is not under routine surveillance,” she told reporters.

‘On the other hand, since it’s such a severe and unusual feature, I would expect it would have been noticed previously,” she added.

Ammon refused to be drawn on whether a possible drop in immunity caused by two years of COVID-19 related lockdown and social distancing could be a factor in the cases, saying “it could be one factor, but I can neither confirm nor deny that because it’s still under investigation right now”.

Hepatitis: What to look out for

Ammon told reporters that the cases of hepatitis had displayed similar symptoms.

“The most common clinical presentation was jaundice – getting yellow in the skin and the eyes – followed by vomiting or gastrointestinal symptoms,” she said.

Ammon’s advice echoed a Monday update from Dr Meera Chand, Director of Clinical and Emerging Infections at the UKHSA, who said parents and guardians should be alert to the symptoms of hepatitis, including jaundice.

“Children experiencing symptoms of a gastrointestinal infection including vomiting and diarrhoea should stay at home and not return to school or nursery until 48 hours after the symptoms have stopped,” Chand said.

The typical patient with unexplained acute hepatitis was a child under 5 years old, the UKHSA said.

Most patients initially suffered from nausea and diarrhoea, and later developed jaundice, the agency added.