‘Showing the truth matters’: Confessions of a war photographer

From 25 January to 8 April 2022, Vadim Ghirda took some of the most powerful and recognisable photographs of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

Initially finding an interest in photography as a way to fit in at parties, Ghirda joined the AP in 1990 when he was just 18 years old.

Since then he’s covered complex social and political conflicts in countries such as Romania, Moldova, Serbia, Macedonia and most recently, Ukraine.

The first days of the Russian invasion found Ghirda in bombarded Kharkiv, Ukraine’s second-largest city, crouching in the snow next to a dead soldier and a destroyed Russian rocket launcher.

Then he was on to Kyiv, the Ukrainian capital, to document the frantic crush of people trying to leave the country while they still could.

He also photographed some of the horrors found in the Ukrainian town of Bucha, where Ukrainian officials say Russian soldiers committed war crimes before withdrawing.

We interviewed Ghirda to find out more about his work and why he believes photography is more important than ever.

firefighter walks outside a destroyed apartment building after a bombing in a residential area in Kyiv, UkraineVadim Ghirda/AP

firefighter walks outside a destroyed apartment building after a bombing in a residential area in Kyiv, UkraineVadim Ghirda/APHow did you get into photography?

“I got into photography as a means to blend in when I was very young. Going to parties you don’t find your place, but if you have a camera you suddenly have something to do and it helps if your people skills are not very good.”

“Also, my mother worked as a photo editor in the local news agency, so I kind of grew up amongst photographers.”

Bogdana, 17, rubs noses with her boyfriend Ivan, 19, in Brovary, UkraineVadim Ghirda/AP

Bogdana, 17, rubs noses with her boyfriend Ivan, 19, in Brovary, UkraineVadim Ghirda/APWhat is the focus of your photography?

“There’s a lot going through my head when I take pictures, beginning with the technical aspects which are obviously very important. But the focus of my photography is people.”

“I’m a person that is happy when emotions are somehow captured or preserved in an image. In photography, I think there is a bit of magic, in the sense that you can achieve, to a certain level, what many people dream about, which is stopping time. And you can really capture an emotion of a fragment of life.”

A Ukrainian firefighter drags a hose inside a large food products storage facility which was destroyed by an airstrike in the early morning hours in Brovary, north of Kyiv, UkVadim Ghirda/AP

A Ukrainian firefighter drags a hose inside a large food products storage facility which was destroyed by an airstrike in the early morning hours in Brovary, north of Kyiv, UkVadim Ghirda/APWhat are the logistics involved with your work?

“There’s a lot of preparation involved. What’s very important is the work of the local journalists or fixers. Everyone that works with you is absolutely crucial. To take great pictures you have to get to the place and you have to have access. And getting that access very often has almost nothing to do with you.”

“When photographing people, my main focus first of all is to intrude as little as possible. You generally get to spend very little time with a person so it can be difficult to gain their trust. For example, you go to visit a trench line position of the army, and you only get to spend maybe one to two hours there. There’s a fine line between starting to work as soon as possible and actually trying to introduce yourself, and make people feel comfortable with you. The minute they sense that you are empathetic with the situation and are actually interested in really telling their story and describing what they’re going through, they start to open up. Once that stage is out of the way, then you can focus on actually taking pictures.”

A 99 year-old woman, traumatised by the Russian occupation, is comforted by her daughter-in-law in Andriivka, UkraineVadim Ghirda/AP

A 99 year-old woman, traumatised by the Russian occupation, is comforted by her daughter-in-law in Andriivka, UkraineVadim Ghirda/APWhat goes through your head when you take photographs?

“Sometimes you feel completely insensitive staring at that person through a camera and taking pictures, while they’re basically falling apart. You witness people sometimes the minute they identity their last relative that they were hoping survived and they realise they didn’t. This is the toughest emotional challenge.”

“A lot of people are saying ‘Vadim, Oh how brave you are doing all this and all that,’ – it’s really not the case. The minute you raise the camera, at least for me, it sort of disconnects you from the feeling of danger or what you would worry about normally if you were just a bystander or if you were really involved in what people do there.”

“I’m worried that it’s going to sound like minimising the actual experience but in many ways, it’s like you’re basically just watching a movie, and you’re trying to frame it as best as possible. I mean there’s a risk in this because sometimes you’re so disconnected and focused on what’s happening in front of you or what you’re trying to get, that you may ignore very visible risks that are coming from behind you or things like that.”

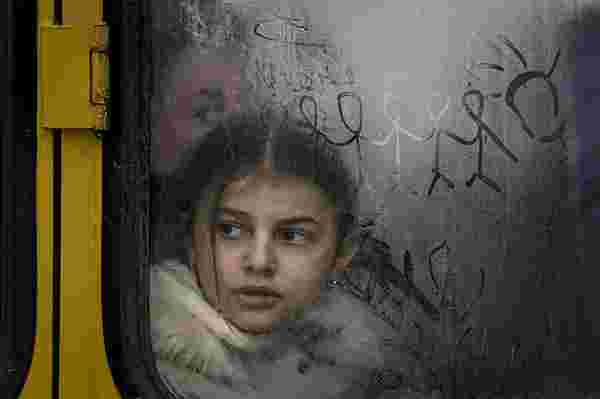

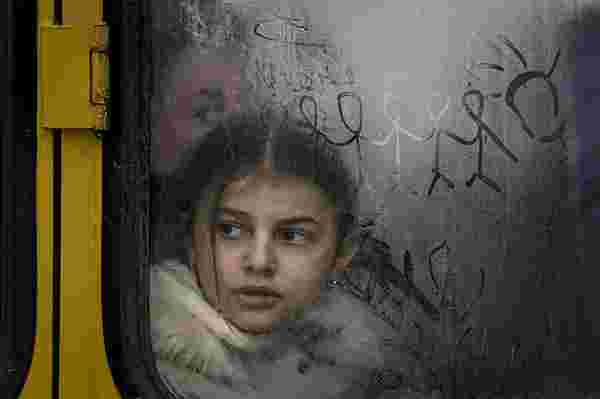

child looks out of a bus window with drawings on it as civilians are evacuated from Irpin, UkraineVadim Ghirda/AP

child looks out of a bus window with drawings on it as civilians are evacuated from Irpin, UkraineVadim Ghirda/APWhy do you think photography is important in times of war?

“The most important thing is the ability to inform the world in real-time about a situation that is happening. Speaking the truth and showing the truth matters, especially in times like now, where the amount of fake information across all these platforms is absolutely scary. Photography is an undeniable source of information. Visual journalism, from reliable sources and done by people who have a moral compass that is absolutely sound, is crucial.”

“My aim with these pictures is to make as many of the people who will see them feel what that person felt or offer them a tool to really experience the tragedy that people are going through. The more people who resonate to what you do and understand what other people are going through, the better it will be. And to achieve that you really need to try and feel what that person feels. If you liberate yourself from prejudice or from ego, you do realise that you are the same as this old lady in Ukraine. You could be in that situation. And hopefully this will make us all better people.”

“So if one image that I shoot, changes the mind of one person, I think I was successful”.

Watch the video above to see the full interview with Vadim Ghirda

From 25 January to 8 April 2022, Vadim Ghirda took some of the most powerful and recognisable photographs of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

Initially finding an interest in photography as a way to fit in at parties, Ghirda joined the AP in 1990 when he was just 18 years old.

Since then he’s covered complex social and political conflicts in countries such as Romania, Moldova, Serbia, Macedonia and most recently, Ukraine.

The first days of the Russian invasion found Ghirda in bombarded Kharkiv, Ukraine’s second-largest city, crouching in the snow next to a dead soldier and a destroyed Russian rocket launcher.

Then he was on to Kyiv, the Ukrainian capital, to document the frantic crush of people trying to leave the country while they still could.

He also photographed some of the horrors found in the Ukrainian town of Bucha, where Ukrainian officials say Russian soldiers committed war crimes before withdrawing.

We interviewed Ghirda to find out more about his work and why he believes photography is more important than ever.

firefighter walks outside a destroyed apartment building after a bombing in a residential area in Kyiv, UkraineVadim Ghirda/AP

firefighter walks outside a destroyed apartment building after a bombing in a residential area in Kyiv, UkraineVadim Ghirda/APHow did you get into photography?

“I got into photography as a means to blend in when I was very young. Going to parties you don’t find your place, but if you have a camera you suddenly have something to do and it helps if your people skills are not very good.”

“Also, my mother worked as a photo editor in the local news agency, so I kind of grew up amongst photographers.”

Bogdana, 17, rubs noses with her boyfriend Ivan, 19, in Brovary, UkraineVadim Ghirda/AP

Bogdana, 17, rubs noses with her boyfriend Ivan, 19, in Brovary, UkraineVadim Ghirda/APWhat is the focus of your photography?

“There’s a lot going through my head when I take pictures, beginning with the technical aspects which are obviously very important. But the focus of my photography is people.”

“I’m a person that is happy when emotions are somehow captured or preserved in an image. In photography, I think there is a bit of magic, in the sense that you can achieve, to a certain level, what many people dream about, which is stopping time. And you can really capture an emotion of a fragment of life.”

A Ukrainian firefighter drags a hose inside a large food products storage facility which was destroyed by an airstrike in the early morning hours in Brovary, north of Kyiv, UkVadim Ghirda/AP

A Ukrainian firefighter drags a hose inside a large food products storage facility which was destroyed by an airstrike in the early morning hours in Brovary, north of Kyiv, UkVadim Ghirda/APWhat are the logistics involved with your work?

“There’s a lot of preparation involved. What’s very important is the work of the local journalists or fixers. Everyone that works with you is absolutely crucial. To take great pictures you have to get to the place and you have to have access. And getting that access very often has almost nothing to do with you.”

“When photographing people, my main focus first of all is to intrude as little as possible. You generally get to spend very little time with a person so it can be difficult to gain their trust. For example, you go to visit a trench line position of the army, and you only get to spend maybe one to two hours there. There’s a fine line between starting to work as soon as possible and actually trying to introduce yourself, and make people feel comfortable with you. The minute they sense that you are empathetic with the situation and are actually interested in really telling their story and describing what they’re going through, they start to open up. Once that stage is out of the way, then you can focus on actually taking pictures.”

A 99 year-old woman, traumatised by the Russian occupation, is comforted by her daughter-in-law in Andriivka, UkraineVadim Ghirda/AP

A 99 year-old woman, traumatised by the Russian occupation, is comforted by her daughter-in-law in Andriivka, UkraineVadim Ghirda/APWhat goes through your head when you take photographs?

“Sometimes you feel completely insensitive staring at that person through a camera and taking pictures, while they’re basically falling apart. You witness people sometimes the minute they identity their last relative that they were hoping survived and they realise they didn’t. This is the toughest emotional challenge.”

“A lot of people are saying ‘Vadim, Oh how brave you are doing all this and all that,’ – it’s really not the case. The minute you raise the camera, at least for me, it sort of disconnects you from the feeling of danger or what you would worry about normally if you were just a bystander or if you were really involved in what people do there.”

“I’m worried that it’s going to sound like minimising the actual experience but in many ways, it’s like you’re basically just watching a movie, and you’re trying to frame it as best as possible. I mean there’s a risk in this because sometimes you’re so disconnected and focused on what’s happening in front of you or what you’re trying to get, that you may ignore very visible risks that are coming from behind you or things like that.”

child looks out of a bus window with drawings on it as civilians are evacuated from Irpin, UkraineVadim Ghirda/AP

child looks out of a bus window with drawings on it as civilians are evacuated from Irpin, UkraineVadim Ghirda/APWhy do you think photography is important in times of war?

“The most important thing is the ability to inform the world in real-time about a situation that is happening. Speaking the truth and showing the truth matters, especially in times like now, where the amount of fake information across all these platforms is absolutely scary. Photography is an undeniable source of information. Visual journalism, from reliable sources and done by people who have a moral compass that is absolutely sound, is crucial.”

“My aim with these pictures is to make as many of the people who will see them feel what that person felt or offer them a tool to really experience the tragedy that people are going through. The more people who resonate to what you do and understand what other people are going through, the better it will be. And to achieve that you really need to try and feel what that person feels. If you liberate yourself from prejudice or from ego, you do realise that you are the same as this old lady in Ukraine. You could be in that situation. And hopefully this will make us all better people.”

“So if one image that I shoot, changes the mind of one person, I think I was successful”.

Watch the video above to see the full interview with Vadim Ghirda